Ever stared at a Stress-Strain Curve and felt like you'd accidentally wandered into a calculus convention? Yeah, me too.

It looks intimidating, all lines and numbers. But relax! It's not as scary as your tax return. (Unpopular opinion: taxes are ALWAYS scary.)

Decoding the Mystery: It's Just a Story

Think of the curve as a story. A story about a material being pushed and pulled. It’s a story of deformation!

Imagine you have a rubber band. You stretch it. That’s the "strain."

The rubber band *resists* being stretched. That resistance is the "stress."

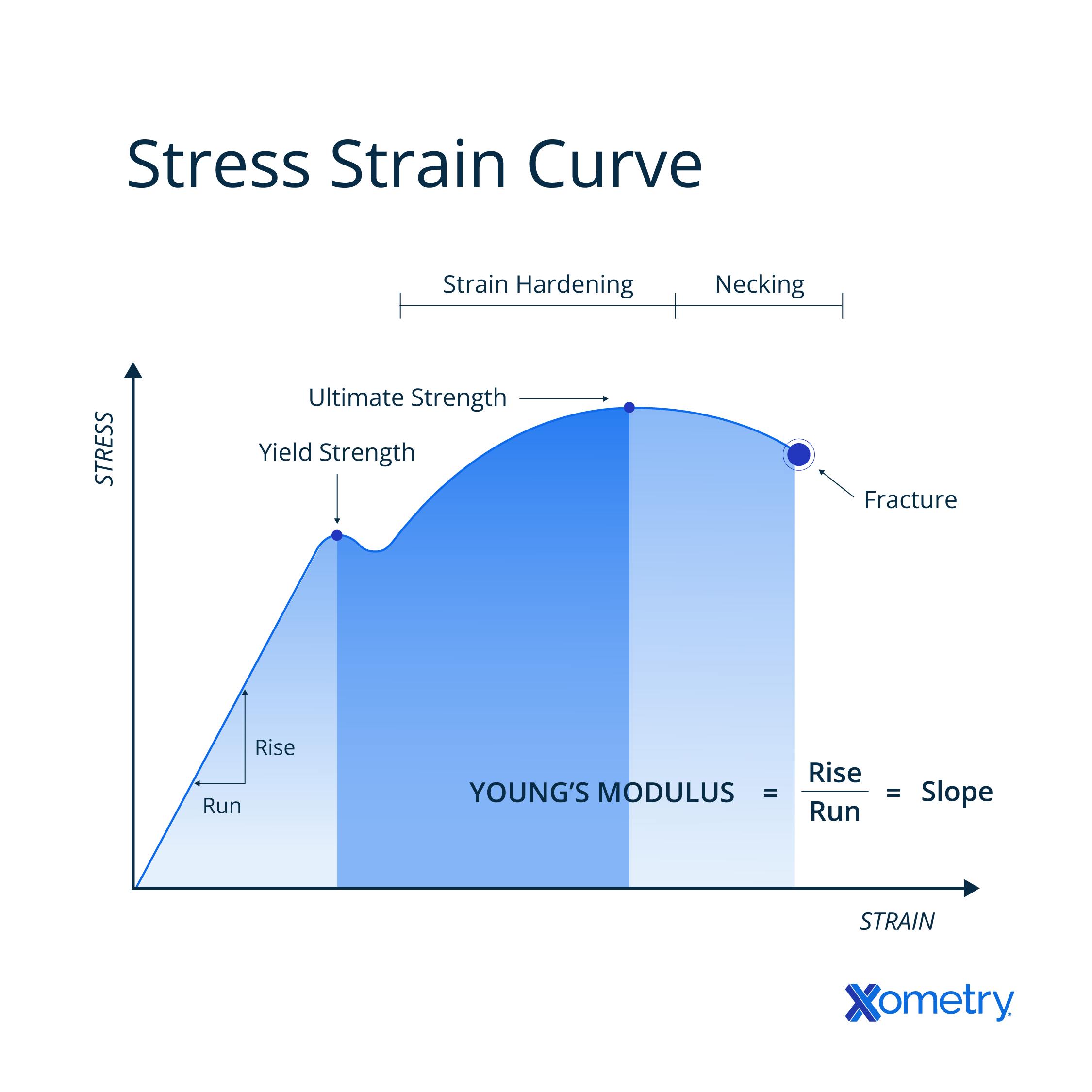

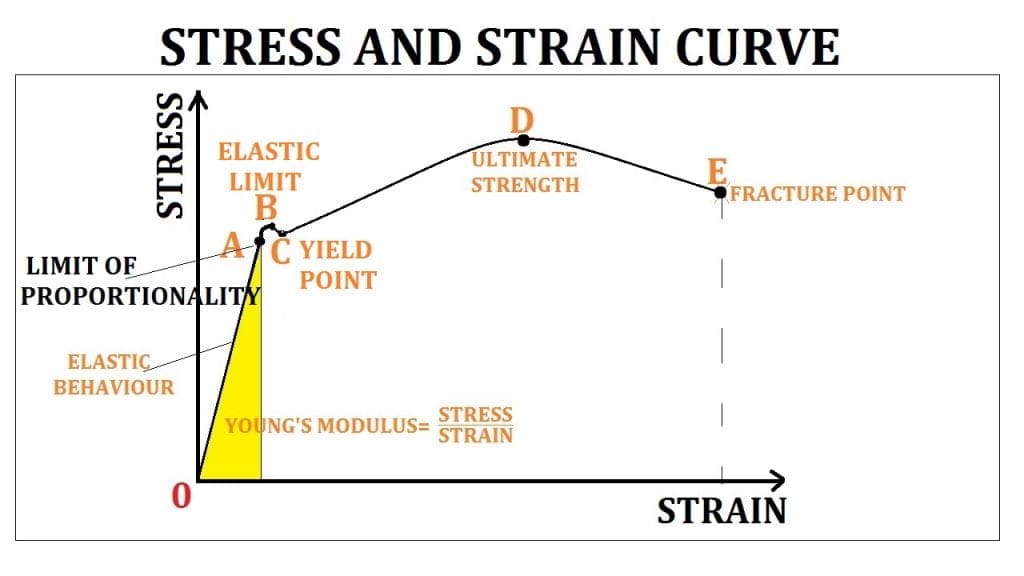

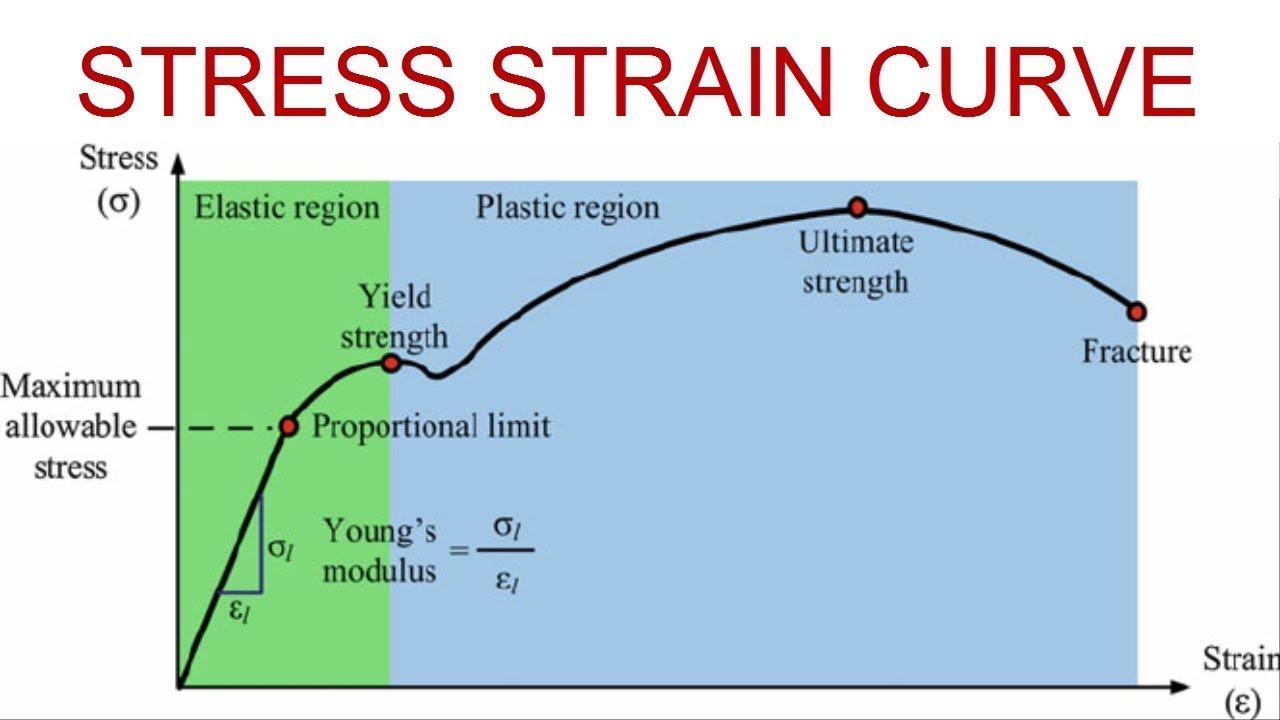

The Straight Line: Hooke's Law and Being a Good Sport

The first part of the curve is usually a straight line. This is where Hooke's Law lives.

Hooke's Law basically says: "The more you pull, the more it resists, *proportionally*." It's a simple relationship.

Think of it like a well-behaved spring. You stretch it a little, it pulls back a little. Stretch it a lot, it pulls back a lot. It's predictable!

This region is called the elastic region. Let go, and the material returns to its original shape.

It's like when you overeat at Thanksgiving. Your stomach stretches (strain), but then goes back to normal(ish) afterwards (elasticity). (Unpopular opinion: stretchy pants were invented *for* Thanksgiving.)

Yield Point: The Point of No Return (Kinda)

Eventually, the straight line bends. Uh oh!

This bending happens at the yield point. This is where things get a little more…permanent.

Imagine bending a paperclip. It bends back a little, but it’s *never* quite straight again. That’s past the yield point.

The material starts to deform *plastically*. That means it won't fully return to its original shape after the stress is removed.

Think of playdough. You squish it (strain), and it stays squished (plastic deformation).

The Mushy Middle: Plastic Deformation and the Struggle

After the yield point, the curve usually flattens out a bit. This is the region of plastic deformation.

The material is stretching a lot without much increase in stress. It's fighting back, but not very effectively.

Think of it like trying to squeeze toothpaste out of an almost-empty tube. You have to work harder and harder for less and less toothpaste.

The material's microstructure is changing. Bonds are breaking and reforming. It’s a chaotic internal dance.

This is the area where materials engineers can do some very interesting things. They can strengthen the material through cold working.

Ultimate Tensile Strength: The Peak Performance

The curve eventually reaches a peak. This is the ultimate tensile strength (UTS).

This is the strongest the material will ever be. The peak is the point where you applied the most stress to the material before it started to fail.

Think of it like a weightlifter reaching their maximum lift. They can't lift any more! Everything has reached the limit.

This is usually the point that engineers are most interested in. They want to know what the maximum stress a material can withstand is.

Necking: The Beginning of the End

After the UTS, the curve starts to go down. This is often due to a phenomenon called necking.

Necking is where the material starts to thin out in one particular area. Like when you stretch a taffy too much, and it gets thin in the middle.

The stress is now concentrated in that thin area, causing it to weaken and eventually fail.

The material is basically choosing its weakest spot to give up.

Fracture Point: Game Over

Finally, the curve reaches the end. This is the fracture point.

The material breaks! Snap! Crack! It's all over. Stress has dropped.

It’s like when you finally pull that rubber band too far. It snaps, and you’re left holding two useless pieces.

The material has completely lost its ability to withstand stress. It's time to start over with a new piece.

What Does It All Mean? Material Properties

The stress-strain curve tells you a lot about a material's properties. It's like a fingerprint. It tells you about:

- Strength: How much stress can it withstand?

- Ductility: How much can it stretch before breaking?

- Stiffness: How much does it resist deformation?

- Toughness: How much energy can it absorb before fracturing?

A material with a high UTS is strong. A material that stretches a lot before breaking is ductile.

A material with a steep slope in the elastic region is stiff. A material with a large area under the curve is tough.

These properties are crucial for engineers designing everything from bridges to airplanes. They need to pick the right material for the job.

Different Materials, Different Stories

Different materials have different stress-strain curves. Steel has a very different curve than rubber.

Steel is strong and stiff. It can withstand a lot of stress before it starts to deform. It is usually brittle compared to rubber.

Rubber is flexible and elastic. It can stretch a long way before breaking, but it is relatively weak.

By looking at the curve, you can quickly tell what kind of material you're dealing with. You can guess its approximate uses and where it could be applied.

Stress-Strain Curves in Real Life

You might think stress-strain curves are only used in labs. You’d be wrong!

They're used in all sorts of industries. From designing safer cars to building stronger bridges. Every application requires its own material property.

Engineers use them to make sure that structures can withstand the stresses they'll be subjected to in the real world.

So, the next time you see a stress-strain curve, don’t panic. It’s just a story. A story about a material being pushed to its limits.

Now, go forth and impress your friends with your newfound knowledge of material behavior! (Unpopular opinion: talking about stress-strain curves at parties is a *great* way to make friends. Maybe.)